Do you have opinions about wine? We here at The Crafty Cask sure do! Are your opinions based on the name, label, grape varietal, bottle shape, or cost? Admittedly, all these elements influence what we decide to select off the shelf. How about cork or screw cap? Do you shy away from some bottles simply because they have a screw cap? If so, you wouldn’t be the first!

Where did the belief that wine with a cork is better come from?

Screw cap wines have become a common topic of discussion since arriving in the wine industry in the 1970’s. In the US, wine bottles with a “Stelvin closure,” more commonly known as a screw cap, are often derided as inferior. Why is this? Many would point to a commonality between screw caps and cheap wine that isn’t entirely unfounded. Once brands of cheap wine like Thunderbird (“What’s the word? Thunderbird! What’s the price? Fifty twice!”) and Mad Dog flooded the market, this association was hard to undo.

Contrary to common belief, however, screw caps don’t inherently indicate sub-average wine. In fact, some studies have shown this enclosure may be superior to cork when it comes to protecting your wine. The movement towards utilizing screw caps began in Australia in the late 1970’s, when Yalumba Winery began using them.

Flawed wine attributed to inferior cork was a prevalent problem in Australia and nearby New Zealand during the 1970s and beyond, likely due to the remoteness of these wine growing regions compared to where the vast majority of cork is grown. Cork comes from the bark of the Cork Oak (Quercus suber), a tree indigeounous to the Iberian peninsula. Portugal and Spain are just about as far away from Australia and New Zealand as you can get, and as a result, wineries there got the dregs of corks produced. Cork, being a natural product, has variances. Excessive variances can lead to flaws in the wine.

DID YOU KNOW?

Wine that is “corked” is just one type of fault found in wine. The aroma of corked wine smells quite muted with little fruit or floral aromas. They also carry a distinct odor often compared to wet cardboard or newspaper. Bottles with “cork taint” are affected by a mold called trichloroanisole, or TCA for short. This mold develops in the presence of chlorine. Since poor quality cork often isn’t visibly appealing, many producers would try to sterilize and clean their corks using chlorine bleach.

At one point in Australia, an average of one bottle per case of wine was flawed. This is a failure rate of nearly 10%, unacceptable in any industry. No wonder they looked for an alternative! The screw cap enclosure swiftly replaced cork for many producers looking to salvage the reputation these flawed wines had created. Sadly, the general public resisted this shift. Perhaps it was because screw caps were adopted earliest by producers of cheap wine who were looking for a more effective and inexpensive means of preserving their wine. So, the perception of screw cap = cheap wine began.

Preservation? What does a cork or screw cap have to do with that?

One primary reason for sealing wine either with a cork or screw cap (other than the obvious purpose of preventing it from glugging out onto the floor) is to prevent oxidation. Oxidation occurs when oxygen in the air interacts with various molecules in the wine and changes them. This effect can easily be seen in wine opened a few days ago which no longer tastes the same. However, oxidation isn’t exclusively bad. One of the positive effects of some oxygen exposure include the release of aromatic compounds when introduced to fresh air. Hence, the common practice of swirling a wine in the glass or decanting a bottle.

Part of the debate regarding corks and screw caps surrounds the effectiveness of preventing oxidation. Cork, while watertight (or “wine” tight), is not airtight. Which means over the course of its life in a cellar, a cork will permit a small transference of oxygen into the bottle (about 1 mg per year). This controlled exposure to miniscule amounts of oxygen is critical in the maturation of many of the world’s most coveted and revered wines, which often age for a decade or more. As a result, producers of high quality, age-worthy wines such as those found in Barolo, Bordeaux, Montalcino, Napa, and elsewhere were wary of using anything other than tried-and-true cork. At least at first.

Skip forward a couple decades to see where the story leads…

In 2000, the prestigious Napa winery PlumpJack decided to bottle half of its 1997 Reserve Cabernet Sauvignon with screw caps. In fact, they charged slightly more ($135 instead of $125) for the screw cap offering. The higher price for the screw cap suggested a guarantee the wine wouldn’t be flawed by cork issues. Additionally, they bundled this premier offering in two-bottle shipments. One bottle with the traditional cork, the other with a screw cap—allowing consumers to draw their own conclusion on the merits of cork vs screw cap. PlumpJack continues to offer their reserve Cabernet Sauvignon in both options. In 2012, Somm Journal hosted a qualitative vertical tasting panel to assess how these wines had progressed. Five vintages over ten years were tasted, both cork and screw cap versions. Impressions of the panelist were recorded and the results revealed.

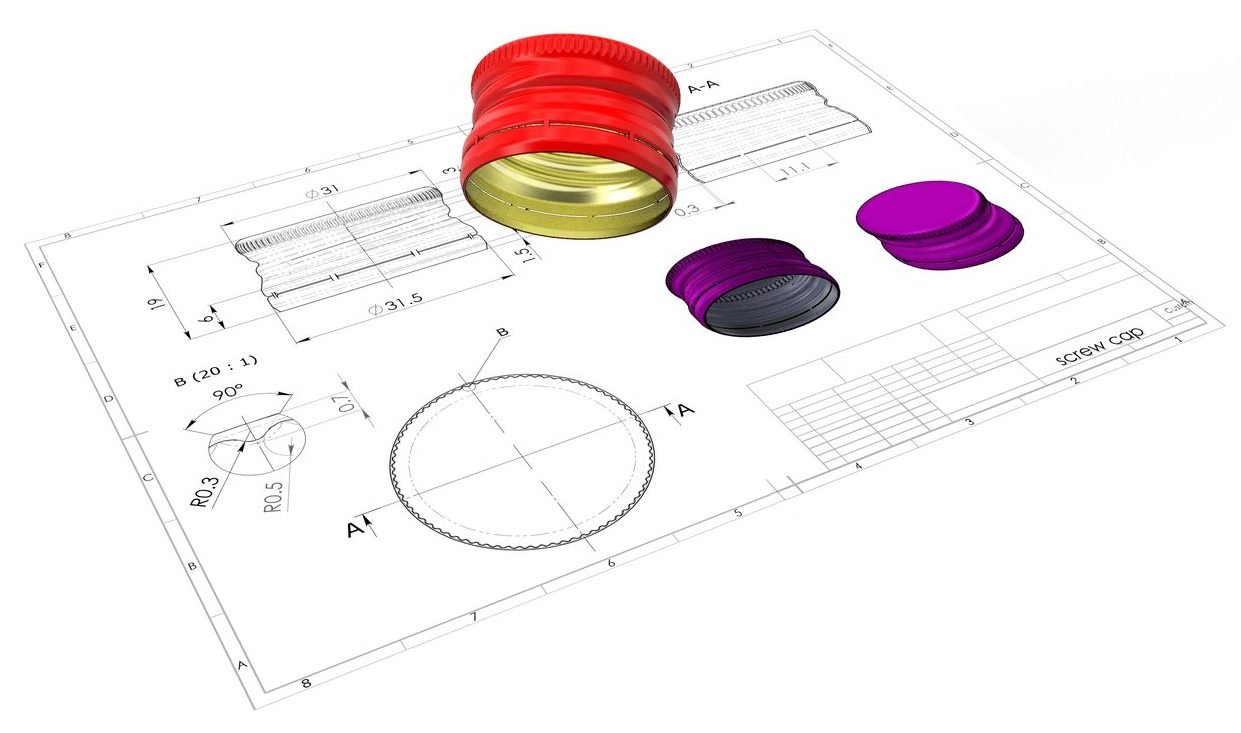

While inconclusive, partially due to the qualitative nature of the tasting, absent was the undesired conclusion that screw caps prevented wines from evolving as cellaring intends. The technology underlying screw caps has continued to progress. While initially these closures sealed hermetically, with no air transfer in or out, this technology improved. The plastic disc at the tops are now permeable and the level of permeability can be chosen. Since this feature is manufactured, it’s uniform across all screw caps, whereas there is variability in natural products like cork. As a result, winemakers who use screw caps can more accurately predict the optimal drinking window for a given wine.